Which of the Following Were Preeminent in the Art of Writing?

History painting is a genre in painting stated as a subject matter rather than creative fashion. History paintings usually depict a moment in a narrative story, rather than a specific and static subject, every bit in a portrait. The term is derived from the wider senses of the word historia in Latin and Italian, meaning "story" or "narrative", and essentially means "story painting". Near history paintings are not of scenes from history, peculiarly paintings from before well-nigh 1850.

In mod English, historical painting is sometimes used to describe the painting of scenes from history in its narrower sense, especially for 19th-century art, excluding religious, mythological, and allegorical subjects, which are included in the broader term history painting, and earlier the 19th century were the most mutual subjects for history paintings.

History paintings most e'er contain a number of figures, oft a big number, and normally show some typical states on that is a moment in a narrative. The genre includes depictions of moments in religious narratives, higher up all the Life of Christ, Middle eastern civilisation also as narrative scenes from mythology, and also emblematic scenes.[1] These groups were for long the near frequently painted; works such as Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling are therefore history paintings, as are most very large paintings before the 19th century. The term covers large paintings in oil on canvas or fresco produced between the Renaissance and the late 19th century, subsequently which the term is more often than not non used even for the many works that still see the basic definition.[ii]

History painting may be used interchangeably with historical painting, and was especially and then used before the 20th century.[3] Where a distinction is made, "historical painting" is the painting of scenes from secular history, whether specific episodes or generalized scenes. In the 19th century, historical painting in this sense became a distinct genre. In phrases such as "historical painting materials", "historical" ways in utilise before about 1900, or some earlier appointment.

Prestige [edit]

History paintings were traditionally regarded as the highest course of Western painting, occupying the well-nigh prestigious place in the hierarchy of genres, and considered the equivalent to the epic in literature. In his De Pictura of 1436, Leon Battista Alberti had argued that multi-figure history painting was the noblest class of fine art, as being the about difficult, which required mastery of all the others, because it was a visual form of history, and because it had the greatest potential to move the viewer. He placed emphasis on the power to draw the interactions between the figures by gesture and expression.[4]

This view remained general until the 19th century, when creative movements began to struggle against the establishment institutions of academic fine art, which continued to adhere to it. At the aforementioned time, there was from the latter part of the 18th century an increased interest in depicting in the course of history painting moments of drama from recent or gimmicky history, which had long largely been confined to battle-scenes and scenes of formal surrenders and the like. Scenes from aboriginal history had been popular in the early Renaissance, and once once again became common in the Baroque and Rococo periods, and withal more then with the rising of Neoclassicism. In some 19th or 20th century contexts, the term may refer specifically to paintings of scenes from secular history, rather than those from religious narratives, literature or mythology.

Evolution [edit]

The term is generally not used in art history in speaking of medieval painting, although the Western tradition was developing in large altarpieces, fresco cycles, and other works, as well equally miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Information technology comes to the fore in Italian Renaissance painting, where a series of increasingly aggressive works were produced, many withal religious, but several, especially in Florence, which did actually feature near-contemporary historical scenes such as the set of 3 huge canvases on The Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello, the abortive Boxing of Cascina by Michelangelo and the Boxing of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci, neither of which were completed. Scenes from ancient history and mythology were besides pop. Writers such equally Alberti and the following century Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists, followed public and artistic stance in judging the best painters higher up all on their production of large works of history painting (though in fact the only modernistic (post-classical) work described in De Pictura is Giotto's huge Navicella in mosaic). Artists continued for centuries to strive to make their reputation by producing such works, oft neglecting genres to which their talents were better suited.

There was some objection to the term, as many writers preferred terms such as "poetic painting" (poesia), or wanted to make a distinction betwixt the "true" istoria, covering history including biblical and religious scenes, and the fabula, roofing infidel myth, allegory, and scenes from fiction, which could not exist regarded as truthful.[v] The large works of Raphael were long considered, with those of Michelangelo, as the finest models for the genre.

In the Raphael Rooms in the Vatican Palace, allegories and historical scenes are mixed together, and the Raphael Cartoons show scenes from the Gospels, all in the One thousand Manner that from the High Renaissance became associated with, and ofttimes expected in, history painting. In the Late Renaissance and Baroque the painting of bodily history tended to degenerate into panoramic battle-scenes with the victorious monarch or general perched on a equus caballus accompanied with his retinue, or formal scenes of ceremonies, although some artists managed to make a masterpiece from such unpromising material, every bit Velázquez did with his The Surrender of Breda.

An influential formulation of the hierarchy of genres, confirming the history painting at the top, was made in 1667 by André Félibien, a historiographer, architect and theoretician of French classicism became the classic statement of the theory for the 18th century:

Celui qui fait parfaitement des païsages est au-dessus d'un autre qui ne fait que des fruits, des fleurs ou des coquilles. Celui qui peint des animaux vivants est plus estimable que ceux qui ne représentent que des choses mortes & sans mouvement; & comme la effigy de l'homme est le plus parfait ouvrage de Dieu sur la Terre, il est certain aussi que celui qui se rend l'imitateur de Dieu en peignant des figures humaines, est beaucoup plus excellent que tous les autres ... un Peintre qui ne fait que des portraits, n'a pas encore cette haute perfection de l'Art, & ne peut prétendre à 50'honneur que reçoivent les plus sçavans. Il faut pour cela passer d'une seule figure à la représentation de plusieurs ensemble; il faut traiter l'histoire & la fable; il faut représenter de grandes deportment comme les historiens, ou des sujets agréables comme les Poëtes; & montant encore plus haut, il faut par des compositions allégoriques, sçavoir couvrir sous le voile de la fable les vertus des grands hommes, & les mystères les plus relevez.[6]

He who produces perfect landscapes is above another who but produces fruit, flowers or seashells. He who paints living animals is more than those who only represent dead things without movement, and as human being is the most perfect piece of work of God on the earth, it is as well certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in representing human figures, is much more excellent than all the others ... a painter who only does portraits still does non have the highest perfection of his fine art, and cannot expect the laurels due to the nearly skilled. For that he must pass from representing a single effigy to several together; history and myth must be depicted; not bad events must exist represented every bit by historians, or like the poets, subjects that volition please, and climbing still higher, he must have the skill to cover under the veil of myth the virtues of cracking men in allegories, and the mysteries they reveal".

Past the belatedly 18th century, with both religious and mytholological painting in reject, there was an increased demand for paintings of scenes from history, including contemporary history. This was in part driven by the changing audition for ambitious paintings, which now increasingly made their reputation in public exhibitions rather than past impressing the owners of and visitors to palaces and public buildings. Classical history remained popular, but scenes from national histories were oft the all-time-received. From 1760 onwards, the Society of Artists of Great U.k., the beginning trunk to organize regular exhibitions in London, awarded two generous prizes each year to paintings of subjects from British history.[seven]

The unheroic nature of modern dress was regarded equally a serious difficulty. When, in 1770, Benjamin Due west proposed to paint The Death of General Wolfe in gimmicky apparel, he was firmly instructed to use classical costume by many people. He ignored these comments and showed the scene in modern dress. Although George III refused to purchase the piece of work, West succeeded both in overcoming his critics' objections and inaugurating a more historically accurate fashion in such paintings.[8] Other artists depicted scenes, regardless of when they occurred, in classical dress and for a long time, particularly during the French Revolution, history painting oftentimes focused on depictions of the heroic male nude.

The large product, using the finest French artists, of propaganda paintings glorifying the exploits of Napoleon, were matched past works, showing both victories and losses, from the anti-Napoleonic alliance by artists such as Goya and J.M.West. Turner. Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) was a sensation, appearing to update the history painting for the 19th century, and showing bearding figures famous only for beingness victims of what was and then a famous and controversial disaster at sea. Conveniently their dress had been worn away to classical-seeming rags past the signal the painting depicts. At the aforementioned fourth dimension the demand for traditional large religious history paintings very largely fell away.

In the mid-nineteenth century there arose a way known as historicism, which marked a formal faux of historical styles and/or artists. Another evolution in the nineteenth century was the handling of historical subjects, oft on a large scale, with the values of genre painting, the depiction of scenes of everyday life, and anecdote. Grand depictions of events of great public importance were supplemented with scenes depicting more than personal incidents in the lives of the great, or of scenes centred on unnamed figures involved in historical events, as in the Troubadour style. At the same time scenes of ordinary life with moral, political or satirical content became often the main vehicle for expressive interplay betwixt figures in painting, whether given a mod or historical setting.

By the later on 19th century, history painting was oft explicitly rejected by avant-garde movements such as the Impressionists (except for Édouard Manet) and the Symbolists, and according to one recent writer "Modernism was to a considerable extent built upon the rejection of History Painting... All other genres are accounted capable of inbound, in one form or another, the 'pantheon' of modernity considered, but History Painting is excluded".[ix]

History painting and historical painting [edit]

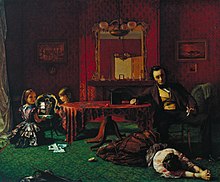

"No. i, Misfortune" from Augustus Egg's By and Nowadays, 1858. The husband has discovered his married woman's infidelity. Prayer and Despair complete the set.

The terms [edit]

Initially, "history painting" and "historical painting" were used interchangeably in English, as when Sir Joshua Reynolds in his quaternary Discourse uses both indiscriminately to cover "history painting", while saying "...it ought to be chosen poetical, as in reality information technology is", reflecting the French term peinture historique, one equivalent of "history painting". The terms began to carve up in the 19th century, with "historical painting" becoming a sub-group of "history painting" restricted to subjects taken from history in its normal sense. In 1853 John Ruskin asked his audience: "What do you at present mean by historical painting? Now-a-days information technology ways the attempt, by the power of imagination, to portray some historical event of past days."[10] And then for example Harold Wethey'due south iii-volume catalogue of the paintings of Titian (Phaidon, 1969–75) is divided between "Religious Paintings", "Portraits", and "Mythological and Historical Paintings", though both volumes I and Iii cover what is included in the term "History Paintings". This distinction is useful merely is past no means generally observed, and the terms are nevertheless often used in a disruptive mode. Because of the potential for defoliation modernistic bookish writing tends to avoid the phrase "historical painting", talking instead of "historical subject field matter" in history painting, only where the phrase is notwithstanding used in contemporary scholarship it volition commonly mean the painting of subjects from history, very ofttimes in the 19th century.[11] "Historical painting" may likewise be used, especially in discussion of painting techniques in conservation studies, to mean "old", as opposed to modern or contempo painting.[12]

In 19th-century British writing on art the terms "subject field painting" or "anecdotic" painting were frequently used for works in a line of development going back to William Hogarth of monoscenic depictions of crucial moments in an implied narrative with unidentified characters,[13] such as William Holman Chase'south 1853 painting The Awakening Censor or Augustus Egg's Past and Nowadays, a set of three paintings, updating sets by Hogarth such every bit Spousal relationship à-la-mode.

19th century [edit]

History painting was the dominant course of academic painting in the various national academies in the 18th century, and for most of the 19th, and increasingly historical subjects dominated. During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods the heroic treatment of contemporary history in a frankly propagandistic fashion by Antoine-Jean, Baron Gros, Jacques-Louis David, Carle Vernet and others was supported by the French country, simply subsequently the fall of Napoleon in 1815 the French governments were not regarded as suitable for heroic treatment and many artists retreated farther into the past to detect subjects, though in U.k. depicting the victories of the Napoleonic Wars by and large occurred after they were over. Another path was to cull gimmicky subjects that were oppositional to government either at home and abroad, and many of what were arguably the last great generation of history paintings were protests at contemporary episodes of repression or outrages at home or away: Goya'due south The 3rd of May 1808 (1814), Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), Eugène Delacroix's The Massacre at Chios (1824) and Liberty Leading the People (1830). These were heroic, merely showed heroic suffering past ordinary civilians.

Romantic artists such as Géricault and Delacroix, and those from other movements such equally the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood continued to regard history painting as the platonic for their most ambitious works. Others such as Jan Matejko in Poland, Vasily Surikov in Russia, José Moreno Carbonero in Spain and Paul Delaroche in France became specialized painters of large historical subjects. The way troubadour ("troubadour mode") was a somewhat derisive French term for earlier paintings of medieval and Renaissance scenes, which were often small and depicting moments of anecdote rather than drama; Ingres, Richard Parkes Bonington and Henri Fradelle painted such works. Sir Roy Strong calls this type of work the "Intimate Romantic", and in French information technology was known equally the "peinture de genre historique" or "peinture anecdotique" ("historical genre painting" or "anecdotal painting").[14]

Church building commissions for big group scenes from the Bible had greatly reduced, and historical painting became very significant. Especially in the early 19th century, much historical painting depicted specific moments from historical literature, with the novels of Sir Walter Scott a particular favourite, in France and other European countries as much equally Slap-up U.k..[15] By the middle of the century medieval scenes were expected to be very carefully researched, using the piece of work of historians of costume, architecture and all elements of decor that were becoming available. And instance of this is the extensive inquiry of Byzantine architecture, clothing and decoration fabricated in Parisian museums and libraries by Moreno Carbonero for his masterwork The Entry of Roger de Flor in Constantinople.[16] The provision of examples and expertise for artists, too as revivalist industrial designers, was ane of the motivations for the institution of museums similar the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[17]

New techniques of printmaking such as the chromolithograph made good quality reproductions both relatively cheap and very widely accessible, and also hugely profitable for artist and publisher, as the sales were so large.[18] Historical painting oftentimes had a close relationship with Nationalism, and painters like Matejko in Poland could play an of import role in fixing the prevailing historical narrative of national history in the pop listen.[19] In France, 50'art Pompier ("Fireman art") was a derisory term for official academic historical painting,[20] and in a final phase, "History painting of a debased sort, scenes of brutality and terror, purporting to illustrate episodes from Roman and Moorish history, were Salon sensations. On the overcrowded walls of the exhibition galleries, the paintings that shouted loudest got the attention".[21] Orientalist painting was an alternative genre that offered similar exotic costumes and decor, and at least as much opportunity to depict sexual practice and violence.

Gallery [edit]

-

-

-

Sebastiano Ricci, Apologue of France as Minerva Trampling Ignorance and Crowning Virtue, 1717–18

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

See also [edit]

- Classicism

- Cobweb painting

- History of painting

- List of Orientalist artists

Notes [edit]

- ^ National Gallery, Glossary entry; History Painting Gallery from The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; Dark-green and Seddon, 7-8; Harrison, 105-106

- ^ Dark-green and Seddon, 11-15

- ^ "History painting". Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary. The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Blunt, 11-12; Barlow, 1

- ^ See Reynolds below; nevertheless he bowed to convention: "In conformity to custom, I phone call this part of the fine art history painting; information technology ought to be chosen poetical, as in reality it is." (Discources, IV); for debates over terminology in the Italian Renaissance, meet Bull, 391-394

- ^ Books.google.co.great britain, translation

- ^ Strong, 17, and 32-34 and generally on growth of historical painting.

- ^ Rothenstein, 16-17; Strong, 24-26

- ^ Barlow, ane

- ^ Lecture IV, p. 172, Lectures on Architecture and Painting: Delivered at Edinburgh, in November, 1853, 1854, Wiley, Internet Archive.

- ^ As shown in the usages in Barlow, Strong, and Wright

- ^ As in "The beautifully renovated Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam will open up its doors to the public in 2013. To gloat this event the Rijksmuseum volition host a three-day symposium on Historical Painting Techniques. The central theme of the symposium will be the technical study of historically used painting techniques, the historical painting materials, their origin and trade, and their application in the painter'due south workshop." Rijksmuseum, "Painting Techniques - Call for Papers" Archived 2013-05-31 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Pamela Grand. Fletcher (1 January 2003). Narrating Modernity: The British Problem Picture, 1895-1914. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 146 note 12. ISBN978-0-7546-3568-0.

- ^ Strong, 36-40; Wright, 269-273, French terms on p. 269

- ^ Wright, throughout; Potent, thirty-32

- ^ "Campaign de Roger de Flor en Constantinopla | artehistoria.com". www.artehistoria.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-11-16 .

- ^ Stiff, 24-26, 47-73; Wright, 269-273

- ^ Harding, vii-9

- ^ Strong, 32-36

- ^ Harding, throughout

- ^ White, 91

References [edit]

- Barlow, Paul, "The Expiry of History Painting in Nineteenth-Century Art?" PDF, Visual Civilization in Britain, Volume 6, Number ane, Summer 2005, pp. ane–13(13)

- Edgeless, Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1660, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-xix-881050-iv

- Balderdash, Malcolm, The Mirror of the Gods, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods, Oxford Upwardly, 2005, ISBN 0195219236

- Green, David and Seddon, Peter, History Painting Reassessed: The Representation of History in Contemporary Art, 2000, Manchester University Printing, ISBN 9780719051685, google books

- Harding, James. Artistes pompiers: French academic fine art in the 19th century, 1979, New York: Rizzoli

- Harrison, Charles, An Introduction to Art, 2009, Yale University Press, ISBN 9780300109153, google books

- Rothenstein, John, An Introduction to English Painting, 2002 (reissue), I.B.Tauris, ISBN 9781860646782

- Strong, Roy. And when did you final run across your father? The Victorian Painter and British History, 1978, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0500271321

- White, Harrison C., Canvases and Careers: Institutional Alter in the French Painting World, 1993 (2nd edn), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226894874, google books

- Wright, Beth Segal, Scott's Historical Novels and French Historical Painting 1815-1855, The Fine art Bulletin, Vol. 63, No. ii (Jun., 1981), pp. 268–287, JSTOR

Further reading [edit]

- Ayers, William, ed., Picturing History: American Painting 1770-1903, ISBN 0-8478-1745-eight

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_painting

0 Response to "Which of the Following Were Preeminent in the Art of Writing?"

Post a Comment